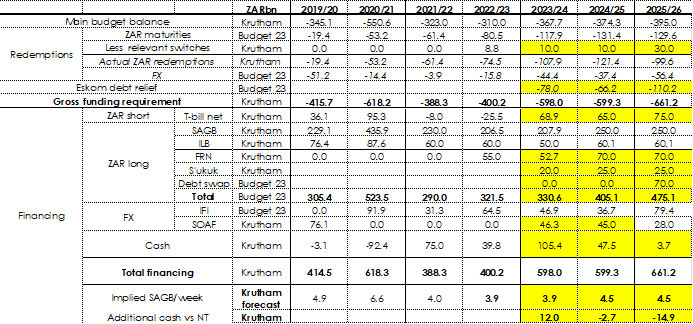

The last blog post on fiscal policy left the big story out. South Africa will have to borrow ZAR1.86 trillion (that’s the one with a “t”), over the next three years or (a somewhat alarming) ZAR283bn more than National Treasury projected on Budget Day 2023.

Where? This blog won’t give you a straight answer because it is not immediately clear that there is that sort of cash lying around to be borrowed. I told you the story of my roadtrip to London - there isn’t much interest in South Africa overseas, so there isn’t much appetite for debt.

But let’s have a look at where Treasury might be able to borrow.

First, how much? A lot. At the time of Budget 2023, National Treasury estimated three-year borrowings of around R1.5 trillion. Krutham’s latest forecast is more like R1.9 trillion. (R1.8585 trillion to be precise). I told you it is a lot.

Gross financing requirement forecast: 2023/24 to 2025/26

Source: Krutham, National Treasury

This translates into an average gross financing requirement of 8.1% of GDP over the next three years. Where will Treasury find an additional ZAR283bn to borrow from, over and above the already quite significant ZAR1.5tn they have pencilled in to raise over the three-year fiscal framework? We look at different buckets of money and conclude that it will be difficult.

Gross financing requirement forecast, by category: 2023/24 to 2025/26

Source: Krutham, National Treasury

This translates into an average gross financing requirement of 8.1% of GDP over the next three years. Where will Treasury find an additional ZAR283bn to borrow from, over and above the already quite significant ZAR1.5tn they have pencilled in to raise over the three-year fiscal framework? We look at different buckets of money and conclude that it will be difficult.

Government debt in perspective

South Africa’s debt can be put in perspective in comparison to the domestic savings base. In Figure 4, we compare total net debt to various pools of capital. Note that the various pools cannot be aggregated – some pension funds hold units in collective investments schemes and banking debt. Collective investment schemes, in turn, hold sovereign debt. We only show the size of the various pools of capital individually.

Nevertheless, immediately, it is apparent how large gross debt is now relative to the various pools of capital. Gross debt is ZAR4.8tn, total private credit extension is ZAR4.5tn, and the total size of the private pensions system is ZAR3.5tn. South Africa’s debt cannot be absorbed by any one of these savings pools.

South African capital markets are deep, but not that deep

Source: Krutham, National Treasury

Ownership of domestic debt is spread out over these different pools (and again, we highlight that there is double counting). We look at the spread of ownership in the next few sections. Then we look at foreign appetite for bonds, before concluding with some observations.

Who owns ZAR bonds?

We dig into this question from two angles – first, who owns the bonds currently? Second, how much spare capacity do they have?

Who owns bonds at the moment?

There is detailed data available from the central securities depository, STRATE, on holdings of ZAR denominated bonds by major type of asset owner. There has been a noticeable decline in foreign holdings – expressed both in relative terms and in absolute terms. In relative terms, non-residents have reduced their holdings from 41.4% in 2017 down to 25.6% as at end 2022.

The relative slack has been taken up by other financial institutions – mainly collective investment schemes (known also as “unit trusts” or “mutual funds”), while the share of bonds from local pension funds has declined.

In the next sections we look at each of these in detail.

Foreign appetite for ZAR bonds has declined, with banks and other financial institutions taking up the slack

Source: National Treasury, STRATE

With the notable exception of the long-dated 2040, foreign participation is toward the short end

Source: National Treasury, STRATE

Non-resident appetite

Non-resident holdings of ZAR debt have declined in relative and absolute USD terms Current appetite for ZAR bonds appears to be weak. In addition to the fall in relative terms highlighted above, it is noticeable that the holdings by non-residents of South African debt have declined in US$ terms. (The rise in ZAR terms naturally reflects the significant depreciation of the exchange rate.)

Holdings of ZAR denominated bonds by non-residents have declined in US$ equivalent

Source: National Treasury, STRATE

South Africa is expected to issue more (as a percentage of GDP) than peers. A key concern for capacity is South Africa’s issuance plans relative to other emerging markets. The IMF (which has a more bearish view on debt plans than us) forecasts that South Africa will need 6% of GDP in 2024 and a similar amount every year until 2028. (This is net lending/borrowing by general government, a different way of calculating than the gross measure we use above).

South Africa’s borrowing requirements are larger than peer EMs, with the exception of Brazil and India

Source: IMF, Government Finance Statistics, IMF. EMDE = Emerging market and developing Economies

The IMF forecasts that with regard to net borrowing South Africa will need more than the EM average, and more than many other peers, with the notable exception of fellow BRICS members, Brazil and India. Given South Africa’s more significant financing needs, it is unlikely that that the offshore bondholders will have appetite for increasing their weightings of South African debt relative to other emerging markets,

Domestic bank capacity

Banks are large holders of government debt. The next place to look at potential capacity is naturally the domestic banks, which are already large holders of domestic debt. South African banks are well capitalised, reasonably profitable and have reasonably large balance sheets relative to the sovereign. Moreover, the regulatory requirements encourage holdings of risk-free government debt (for now).

The share of banks’ assets in sovereign debt has risen since 2008

Source: SARB BA900

Bank capacity is increasingly stretched. While banks are required to hold short-term debt for regulatory purposes, all banks are now comfortably ahead on the liquid coverage ratio (LCR). A Sarb working paper estimates that South African banks are comfortably in excess of their liquid asset requirements. High quality liquid assets (HQLA) have increased by 142% between January 2015 and May 2021. They estimate the Net Stable Funding Ratio and LCR ratios to have been comfortably met, suggesting that there is not much additional appetite for additional short-term debt for regulatory purposes. This is borne out by the stable ratio of the share of bank assets in relatively short-term debt.

Government securities have recently become less attractive relative to government bonds

Source: SARB BA120

Sovereign debt is increasingly unattractive. As the repo rate rises, banks earn more on gross loans and advances (most of their lending book is variable rate, whereas most sovereign debt is fixed rate) unless, of course, yields on government debt rise or floating rate notes (FRNs) are expanded. We can see this in Figure 9, which calculates a naïve effective return on loans and advances versus an effective interest rate earned on sovereign bonds. The sovereign bond earning potential is much less interest rate sensitive – fixed rate instruments by definition are, well, fixed rate, while lending activities are variable rate. This may change as the top of the interest rate cycle arrives – bond prices will rise, and bonds may become relatively more attractive again.

New capital buffers may also discourage sovereign bond holdings. Banks on the internal ratings-based approach (the IRB approach) have seen increased risk weights for sovereign exposure up to 10%. This follows higher public debt and weakening credit ratings. Bond valuation may also become more volatile. There is also the risk of a sovereign-bank nexus similar to that of Silicon Valley Bank where there are large valuation losses. (The IMF estimates that the four larger banks mark-to-market about half of their government bond holdings).

Thus, while there is balance sheet capacity, there is likely not to be risk capacity. With total holdings of sovereign bonds reaching 16%, and concerns about mark-to-market losses arising from onward rises in yields, bank capacity is increasingly stretched.

Moreover, crowding out is a very serious risk. As issuance increases (and yields rise), banks will find sovereign bonds attractive, and more attractive from a profitability perspective than lending. Classic crowding out.

Collective investment schemes (“unit trusts” or “mutual funds”)

Assets under management of the collective investment schemes industry were ZAR3.36tn at the end of the second quarter of 2023. In the year to June 2023, inflows were ZAR567.3bn while outflows were ZAR577.7bn, giving net outflows of ZAR10.4bn. For money market funds, which are most significant holders of government debt, inflows were ZAR325m and outflows were ZAR326m, giving net outflows of ZAR1.5m.

This highlights that the savings base is only slowly rising… Not at all at rates required for meeting the additional gross debt requirements.

Inflows into money market funds - large holders of government debt - are weak

Source: ASISA CIS statistics (Various)

The Sarb data shows that approximately 14% of collective investment schemes assets are in public-sector securities. This would include other large public sector debt issuers, including Eskom and Transnet.

Share of collective investment scheme assets in public sector securities has risen since 2008

Source: SARB Quarterly Bulletin (s-38)

The Government Employees Pension Fund

One of the largest pools of money is under the control of the Public Investment Commissioners including the Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF), the Unemployment Insurance Fund and the Compensation Fund. Total assets rise to ZAR2.3tn of which about 90% are from the GEPF.

There has been a marked shift in asset holdings of the PIC since democracy. Equity ownership has risen from zero percent to approximately 60% of assets. This has been in part due to the exposure of the fund to fast growing shares, including Naspers.

Assets of the PIC have risen sharply and are increasingly in equity

Source: Sarb QB (S-39)

The PIC could be a source of ZAR debt take-up. It has long-dated liabilities (the rules governing it are within the control of the government). The pension fund, however, is independent and faces fiduciary responsibilities to spread its assets across a variety of different instruments. It is, however, not subject to the Pension Funds Act nor to Regulation 28, and its investment policy is at the discretion of the GEPF Board (not the PIC board). (The investment policy is available here). Its asset benchmarks are set out in the Figure below.

GEPF strategic asset allocation is to limit exposure to government bonds

Source: GEPF

Currently, the strategic allocation percentage to government bonds is 31%, which has been the level for quite some time. An increase to the maximum under the investment policy (40%) would imply capacity of approximately ZAR225 bn or a third of financing needs, suggesting that the GEPF is still a source of borrowing capacity, even within its existing guidelines.

That said, one of the unintended consequences of the wage freeze has been that inflows to the GEPF are slowing. Members pay 7.5% of pensionable earnings to the scheme and the employer makes a similar contribution. With overall wage growth being reduced, the outcome is that inflows are rising less quicky at approximately ZAR87bn per year, down from ZAR89bn in 2021. This makes the fund more reliant on returns.

GEPF contributions have tapered off as government wage growth has slowed

Source: SARB QB S-45.

Private pension funds

Private pension funds are a final potential source of additional onshore capacity. However, the data should be treated with care. Much of the pension fund money is directed into collective investment schemes and/or life insurance policies. Thus it is not to say that there is additional capacity – rather the different “pots” are largely the same pot.

The share of pension fund assets in public sector securities has remained around 20%

Source: SARB QB S-45. We use a simple “look-through” and include public sector securities held in insurance policies held by pension funds. This is not an accurate estimate as it may vary but is indicatively correct.

How much additional appetite is there? Private pensions have around ZAR3.5tn of assets and so any additional appetite would be a very, very maximum of say 50% of assets. This would be ZAR1.75tn or just less than that currently held by pension funds.

What is the demand for Eurobonds?

South Africa has traditionally issued a relatively small volume of non-ZAR denominated Eurobonds. The internal benchmark is around 10%. To some extent, IFI borrowing has led to that rising, but it is still low by international comparison. Indeed, one of the strengths of the South African fiscal position has been the ability to reduce the share of foreign debt from peaks of around 20% to 10% by 2022.

In Figure 14, we dig into the quantum of foreign debt issued by South Africa. The time-series differentiates between “marketable” and “non-marketable” debt. The former is typically the usual foreign currency denominated Eurobonds, while the latter is a catch-all for various direct placements, typically international financial institutions (IFI) or special development finance institutional bonds, such as concessional finance relating to climate change.

There are two sharp increases in non-marketable debt – in 2002 and then again in 2020. The 2002 increase was due to the controversial arms deal and related financing – for more details see Table 5.8 of the 2003 Budget Review here. The 2020 increase is naturally due to the additional financing the country took on during the COVID period.

How much demand is there for South African foreign currency debt? Foreign currency debt ownership statistics are not available for the full stock (Bloomberg provides ownership details for approximately 30% of the stock), and so it is difficult to conclude how debt is held. Anecdotal evidence suggests that there has been a shift out of long-only pension funds into more speculative funds, and even into hedge funds based on potential long-term risks.

FX debt has risen to USD20bn, with a large share of “non-marketable (IFI) debt

Source: Sarb QB S-57

The appetite for debt can be derived from standard market statistics, including the cross-currency basis point spread, credit default swap (CDS) spreads, and the breakdown of the different risk premia. While CDS spreads theoretically show the cost of insuring against a default, in practice they provide a good barometer for relative attractiveness of debt. And by this measure, South Africa’s CDS spreads are second only to Turkey in a basket of peers. Moreover, most peers have seen CDSs fall – in contrast South Africa’s are unchanged.

South African CDS spreads are high relative to peers and cross currency spreads have risen

Source: Bloomberg

Anecdotal evidence also doesn’t suggest much appetite from foreign investors at the moment for Eurobonds. We recently did a tour of some institutional investors in London and found the general vibe was “meh” – or indifference to South Africa and South Africa’ narrative. There is no default on the horizon, so hedge fund managers don’t see a need to short; there is no major upside surprise coming on revenue, so long managers don’t see the need to hold long debt. There is, of course, always appetite for high-yield bonds in hard currency. But the risks (and costs) of a substantial expansion of SOAF issuance need to be weighed against the benefits.

Expanding issuance of IFI debt (particularly concessional debt) is tempting but risky. Other African countries have become attached to low-rate concessional IFI funding, but this needs to be rolled over. Often at much higher rates or with the IFIs again. This creates a doom-spiral where the country becomes locked into an IFI lending programme, which creates moral hazard on both sides.

Conclusion

In short, with the fiscal position deteriorating, additional bond issuance is now a near certainty. Our estimate is that National Treasury will have to issue ZAR1.86tn over the next three years.

It is difficult to see where this will be issued. While South Africa has deep and liquid capital markets, such a sheer volume of debt may be difficult to issue even before we consider crowding out effects and the like.

South Africa has a structurally weak savings base. What this means in practice is that the big balance sheets of pension funds and banks are just not growing fast enough to absorb new issuance. The consequence is crowding out – money is diverted from lending to productive activities towards the government (and we know from the government statistics into consumption). This is at the heart of the fiscal problem – borrowing is simply not going into growth-enhancing investment which means that we are stuck.

This is the essence of our fiscal trap and why consolidation is so crucial beyond the narrow arguments of cutting this or that but to allow private sector growth and investment not to be impeded. Note we do not see tapping PIC or GFECRA as a viable option in the policy mindsets of NT (or SARB, or PIC).

Meaningful shifts in the coming horizon of three years are unlikely or at best slow and as such an outlet for further issuance will have to be found – and wherever it comes will mean at higher interest rates – and that seems most likely in hard currency with SOAF.