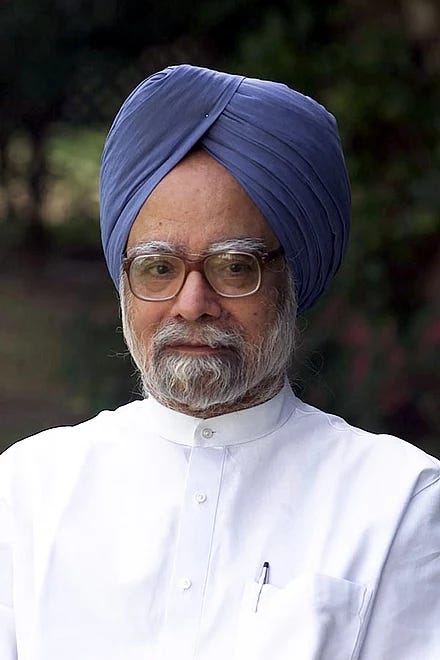

Manhoman Singh passed away on 26 December 2024. He is arguably one of the most consequential policy makers in history — leading what is now the world’s most populous country through a series of reforms. He was Governor of the Reserve Bank of India from September 1982 to January 1985, Finance Minister from June 1991 to May 1996 and Prime Minister from May 2004 – May 2014.

This is an edited repost of a blog from earlier this year on India. It is based on the section in India from my book, How To Fix (Unf*ck) a Country, available at Exclusive Books, Takealot, and other good bookstores. Loot currently has the books at 20% off.

India is an extraordinary case study. Some quick facts:

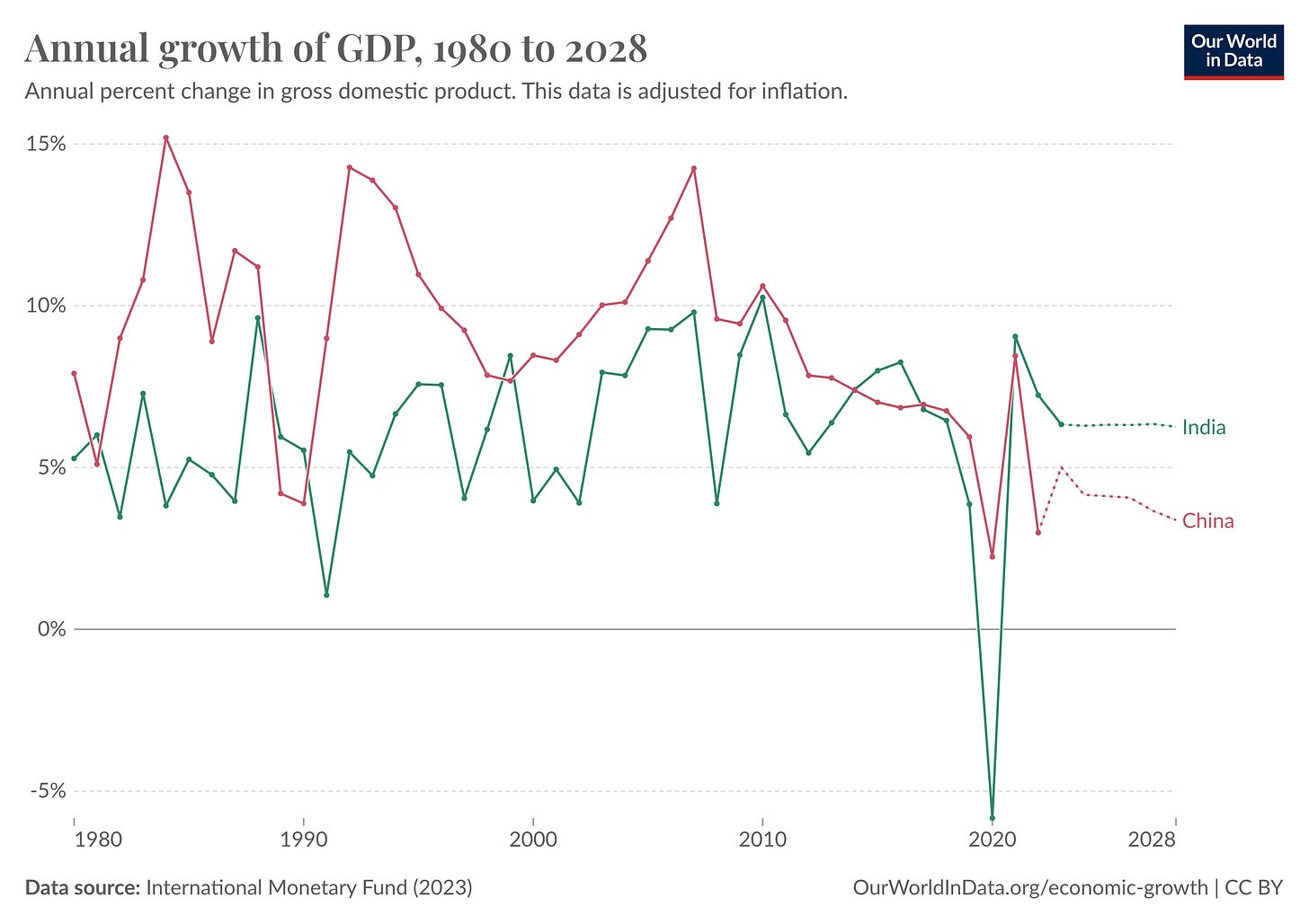

It is projected to grow faster than China over the next few years

It has a population of over 1.4 billion and a poverty rate of 12 per cent, meaning that around 170 million people are poor. This is a number that only really hits home when you are actually there.

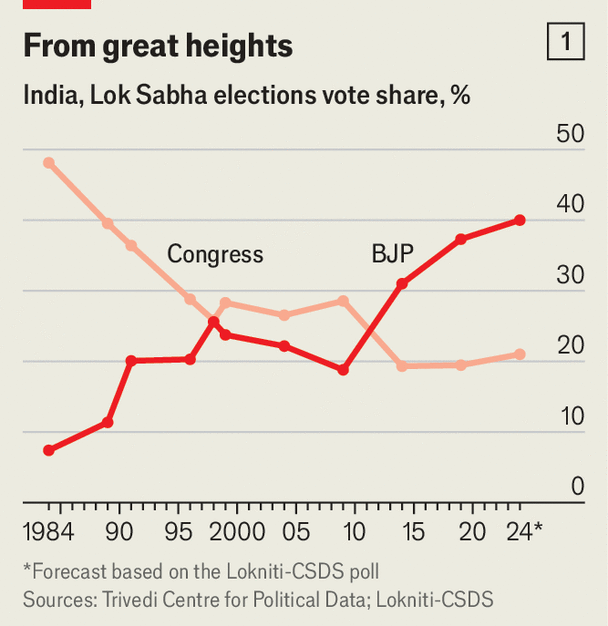

In 1977, the Indian National Congress lost power for the first time, 30 years after independence. From then on, they came and went in and out of power, and indeed it was Congress that adopted an economic reform programme in 1991.

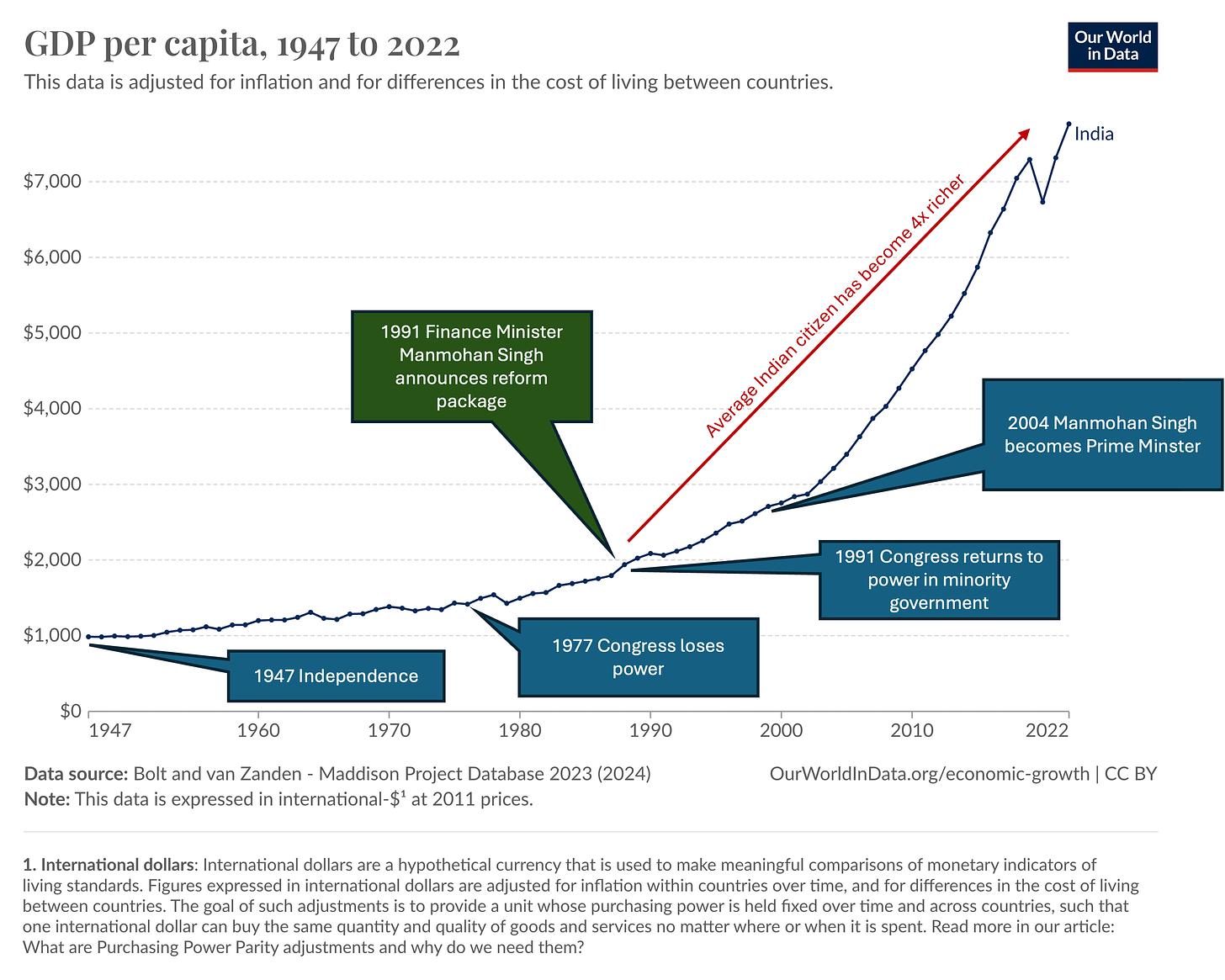

The GDP per capita graph below shows what happened in India. After independence in 1947, the economy muddled along. Singh became finance minister in 1991 and Prime Minister in 2004. Between 1991 and today, GDP per capita in India has nearly quadrupled.

Comparisons with China are often drawn. Both countries grew very fast, but China consistently grew much faster. In the years ahead, India is now expected to grow faster.

… but if you look at per capita terms it is still “catching up” to China.

(Of course, this graph tells us a few things about South Africa: (i) we were richer per capita than China until 2014; (ii) we are still richer on average than India; and (iii) our rapid post-1994 growth came to a shuddering halt in 2008).

So what happened in 1991?

In 1991 India ran out of money, completely. The economy had been so mismanaged that creditors demanded that the gold reserves of the country be handed over physically. The Indian government had to transport forty-seven tonnes of gold to London, and twenty tonnes to Switzerland. And not only that but, as we are told by Y.V. Reddy, the Governor of the Indian Central Bank from 2003 to 2008 and an official at the Bank in 1991,[i] on the road to the airport, in the middle of the night, the truck transporting the gold burst a tyre. Petrified by what might happen, armed guards surrounded the truck, which now stood marooned in the street. Finally, the tyre was fixed, and the gold was safely taken abroad. For many, this moment – when the gold reserves of India were being furtively removed from the country in the middle of the night – represents one of the lowest points in India’s long and complex economic history.

The year 1991 also marked a low point in the political history of the nation. On 21 May 1991, Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated in a suicide bombing. Gandhi had been prime minster from 1984 to 1989. He was the son of Indira Gandhi, prime minister before him until she was also assassinated, and the grandson of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister after Independence. The death of Nehru’s grandson was a deeply distressing moment.

The 1991 crisis had been a long time in coming. In the years before 1991, India had been spending significantly more than its tax revenues. India’s fiscal deficit was 8.4% of GDP. Government debt ballooned. Imports also significantly exceeded exports, leading to a current account deficit. These ‘twin deficits’ left the country vulnerable to a shock. And soon the shock came. In 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, thereby triggering the Gulf War and, with it, a tripling of the oil price. In turn, the United States went into recession, as did all the main oil-importing countries. India’s foreign exchange reserves plunged and soon it was deep in debt. The only way India could meet its obligations was to pledge its gold to its foreign creditors. And so the gold had to be sent to London and Switzerland, in a truck that burst a tyre.

Unsurprisingly, this deep economic crisis had led to end of the dominance of the Indian National Congress, known to most as the Congress Party of India, the party of Mahatma Gandhi and Nehru, which had run India for the majority of the time of Independence in 1947 until they lost the 1989 elections. Not for the first time in history, a liberation party found itself out of power because of bad economic policy.

It was the elections in 1991 were an extraordinary turning point. In 1991, the Indian National Congress scraped 36% of the vote. It managed to put together a minority government.

Manmohan Singh, the new Minister of Finance, was faced with a daunting list of things to do. He decided to stop trying to prop up the value of the currency, the Indian rupee. At first it plunged but then stabilised. A year later, a dual exchange rate system was put in place, and from March 1993 the exchange rate was allowed to find its level more freely in a ‘managed float’.[ii]

But it was the reforms to the red tape in which India was tied that made the real difference. The pre-1991 India was known as ‘the Licence Raj’.[iii] Before the great reforms, if you wanted to do anything, you needed a licence. There were up to eighty different government agencies involved in issuing permits and approvals. Imagine dealing with so many bureaucrats – and, of course, imagine the possibility of one or two of them demanding a bribe to make things happen faster. The more laws and regulations you have, the easier it is for the system to become corrupt.

The complexity of the system, which had tied up everyone in knots, was gradually unbound. The economy was also freed in other ways. Tariffs were reduced.[iv] Until then, the average tariff in 1990 was 56%, though the maximum was as high as 535%. Most goods had a tariff of 100%, doubling the cost to the end consumer. Before 1991, India had a list of items that specified what could be imported. The new rule was that anything could be imported, except for dangerous goods. This simplified trade significantly. At the same time, rules prohibiting foreign investment were scrapped, and foreign direct investment was encouraged in high-technology and high-investment industries.

In addition, the government announced a new industrial policy on 24 July 1991, which deregulated industry and rolled back the Licence Raj.[v] Licensing was abolished in an estimated 80% of industries. The need for prior approval to expand or diversify businesses was removed. Restrictions on the industries in which private companies could operate were reduced. As for publicly owned entities, shares in them were sold off. Much as in China, more autonomy was given to existing public sector enterprises to make for less political interference.

The results have been extraordinary. Dismantling the byzantine and archaic world of the Licence Raj with all its restrictions and confusions, as well as opening up India to the global market, quickly unlocked rapid economic growth. The idea was for the government to step back from meddling in every part of the economy, and to allow Indian businesses to find their own comparative advantage in the world. Here the parallels with China are obvious. As a result India has become a major trading hub for the world.

The effects of all this on the Indian citizenry have been spectacular. From 1991 to the present day, income per capita in India has increased by 350%. Between 1980 and today, the average Indian citizen has gone from earning $1,500 to $6,800 per annum. Gurcharan Das, an Indian author and businessman, has described the great sweep of reforms in the 1990s as ‘though a second independence had arrived: we were going to be free from a rapacious and domineering state’.[vi]

As we have seen, strong finances were key to India’s growth. The country had run out of money but once that problem was fixed, and an economic reform programme was put in place, many of the other problems that India faced could be .worked on.

Our lesson from India is a pretty obvious one: bureaucracy kills an economy. And the other related one, which that state-owned companies often do more harm to an economy than help it. We will see how in many countries, rolling back state-owned enterprises helped growth.

The reforms were not all good

The reforms laid the foundation for rapid economic growth and global integration, they also brought challenges that have persisted or evolved over time. This included a widening of the urban-rural divide. Travelling through India, the sheer number of people in urban areas is mindblowing and the cities are buckling under the strain of rapid growth and development, while rural areas have been left behind, leading to significant disparities. Spatially this holds true too: states with better infrastructure and institutions (like Maharashtra, Karnataka) attracted more investment compared to less-developed states, exacerbating regional disparities. And, of course, the rise of a wealthy corporate elite increased the wealth gap, with benefits of economic growth not equally distributed. I come back to this conundrum in a separate chapter on Equality, but for now it is important to flag this issue.

But, the bottom line…

In 1993-94, the poverty rate was approximately 45.3% based on the national poverty line (Tendulkar Committee Methodology). By 2011-12, this figure had fallen to about 21.9%, according to the same methodology.

By some estimates, in the first twenty years, the 1991 economic reforms lifted 137 million people out of poverty

In 1993-94, around 407 million people were below the poverty line. In 2011-12, this number reduced to about 270 million. Thus, the decline from 1993-94 to 2011-12 translates to roughly 137 million people moving out of poverty.

And what’s next?

India’s economy is not only growing faster than China, it’s population is now larger. This is in part because China’s population growth is slowing — fertility rates have been low since the introduction of the one-child policy in 1979 (lifted in 2015).

India now has an estimated 1.44 billion people to China’s 1.42 billion. Put another way, India has roughly 20 million more people than China, roughly equivalent to the population of Gauteng and Limpopo combined.

A recent Twitter war involving Elon Musk and Vivek has highlighted the role of Indian expats in driving tech innovation in Silicon Valley - with up to 40% of CEOs being of Indian origin.

The United States issues around 279,000 H1-B visas or 72.3% of all H1-B visas to people of Indian origin, and one million visas to Indians overall.

And the future? As the chart below shows, the interesting thing is that the Indian economy is still quite small compared to the US and Chinese economies. And remember, that its population is as big as China. So India still has a lot of potential.

With the right policies, there will be no stopping India.

[i] Y.V. Reddy (2018). Advice and dissent. New Delhi: HarperCollins India.

[ii] I. Patnaik and A. Shah (2012). Did the Indian capital controls work as a tool of macroeconomic policy? IMF Economic Review, 60 (3), 439–464.

[iii] S.W. Sanders (1977). India: Ending the permit-license Raj. Asian Affairs: An American Review, 5 (2), 88–96.

[iv] Intermediate goods had tariffs of 146.4%, capital goods 107.3%, consumer goods 140.9% and manufacturing goods 107.3%.

[v] India before 1991 website, the 1991-economic-reforms

[vi] Gurcharan Das (2000). India unbound: a personal account of a social and economic revolution. New York: Knopf.

Thanks so much for this post, Roy.