Didn’t make the cut for an invite to Jackson Hole last weekend? Don’t worry neither did I, but I have read the papers this and watched what I could on YouTube, so it was like being there. Sort of.

“Jackson Hole” is technically the annual symposium of the Kansas City branch of the Federal Reserve held at Jackson Lake Lodge near Jackson Hole in Wyoming. It became popular once Paul Volcker started attending and speaking. It seems he actually wanted to enjoy the great fly fishing in the area, which is held in late August. It is also, interestingly, one of the least equal places in the whole United States, in part because of Wyoming’s very generous tax regime.

For the market, the highlight is the address by Jerome Powell, Chair of the US Fed, which signals the direction of monetary policy. It added a cool new quote - he said we are “Navigating by the stars under cloudy skies”, which is about the only interesting thing in the whole speech. This is a good thing - there were no surprises.

For macroeconomists, of more interest is the conference itself. Previous conferences have included pathbreaking papers on central banking at low interest rates, balance sheet policy as a tool for central banks and the macroeconomic dilemmas facing emerging markets.

So the academic side can be a big deal - even if the papers don’t become famous, then often it is a very high profile event.

This year, the purported theme of Jackson Hole was “structural shifts”. But going through all the papers, the actual theme was debt and growth, both of which are of local relevance. Three papers touched on a common theme that we are at an inflection point in the global structural macrofinancial cycle – where are we in the cycle of growth, interest rates and debt? Darrel Dufflie of Stanford sounded the alarm about the US Treasury market, noting that the amount of US Treasury bonds is rising rapidly relative to market capacity. Barry Eichengreen highlighted that the world is carrying a lot of debt and this is likely to remain for quite some time, with long run consequences. Charles Jones expressed concern about the slowing of US productivity growth which he linked to slowing innovation.

Below, the highlights package: the Powell address and a quick summary of the three papers.

Jerome Powell’s address and the impact on monetary policy

Powell’s address has been extensively covered in the media, and by other bloggers, so I won’t regurgitate it here. The key points that came out were his resolute statement that “We are prepared to raise rates further if appropriate, and intend to hold policy at a restrictive level until we are confident that inflation is moving sustainably down toward our objective.” The market read this to mean that the Fed believes inflationary pressures remain and that the Fed would only reduce rates slowly and in the classic “data dependent way”. Following the speech, benchmark 10-year yields were 4.27%, up only 4 basis points. The 2-year was at 5.09%, up only 7 basis points. So the market didn’t really react.

US yield curve, 1 August 2023 versus 28 August 2023

Source: US Treasury

No surprises in his speech. It also did not give new insight into a key question that markets are grappling with – how far are we from the top of the US Fed rate cycle?

The US yield curve does seem to suggest that rates are high and likely to fall, while demand indicators remain very strong. The yield curve remains inverted, largely because the market is pricing in that we are at the top of the cycle and, not, we think because there is a US recession coming. At this stage (touch wood) it is likely to be a soft landing.

The US labour market remains tight. Unemployment rate eased to 3.5% in July 2023 (3.6% in June). The “U-6 unemployment rate”, which also includes people who want to work, but have given up searching and those working part-time because they cannot find full-time employment, fell to 6.7% in July (from 6.9%). The labour force participation rate is at its highest since March 2020 (62.6%).

This is not new – there is no reason to expect any interest rate reduction quite yet. Powell’s speech does not change our view on US rates, which is that they will slowly start declining in late 2024 as the lagged impact of an unprecedented tightening of monetary policy feeds through to growth and inflation.

Now turning to the academic part of the conference. It was dominated by concerns about high debt levels and slow global growth. This manifests in a US Treasury market that is not terribly functional.

Paper 1: Structural shifts in the US bond market

In his paper, Darrel Duffie from Stanford University sounds the alarm about the functioning of the US Treasury bill market, saying that current intermediation of the US Treasury market “impairs its resilience.” Risks include losses of market efficiency, higher costs for financing US deficits, potential losses of financial stability, and reduced safe-haven services to investors.

It is the last part that is of most concern – US Treasury debt is an important safe having asset during periods of extreme volatility. The key concern is primary dealer market capacity, which Dufflie shows is under strain. The ratio of US Treasury securities outstanding to primary dealer assets has risen significantly.

The ratio of US Treasury securities outstanding to primary dealer assets has risen significantly

Source: Dufflie (2023)

The paper raises a very important dilemma. Dufflie highlights that the consequence of tighter regulatory requirements on banks has “reduced the short-run flexibility of liquidity provision”. With US debt levels rising and US primary dealers having less flexibility, the consequences are a sudden market event could have severe implications – the US Treasury markets would simply not be able to fulfil its traditional role to the global financial system of providing liquidity.

The dilemma is that the very liquidity regulations that should be increasing financial market resilience may be making the Treasury bond market more fragile, with the unintended consequence of reducing resilience.

The COVID shock is a case in point. There was quite a significant dislocation of Treasury markets around the world. Liquidity dried up significantly – including in South Africa. Central banks intervened. (A Sarb working paper on the South African experience by Roy Havemann, Henk Janse van Vuuren, Daan Steenkamp and Rossouw van Jaarsveld is here).

Perhaps if liquidity regulations had been less stringent, the Treasury bill market would have functioned better? It is difficult to establish this but his conclusion that individual bank regulations may be harmful to overall financial stability should lead to global financial committees taking note.

His core recommendations are to broaden central clearing (i.e., create a mechanism where trades are cleared), all-to-all trading (all-to-all trading would allow any market participant to trade directly with any other market participant), phasing out the US Supplementary leverage rule and some of the GSIB scoring requirements. This could be particularly helpful in times of stress, when the capacity of traditional intermediaries may be tested. A final recommendation is to introduce a clearly articulated market function purchase function programme. (Our paper showed that it was actually the announcement by the Sarb that they would intervene that cause the market to calm down).

Paper 2: Structural shift to high public debt

A second, related theme is on the structural consequences of persistently high debt levels. In particular, debt levels in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Central Asia/Middle East have risen faster than the overall emerging market level and these debt levels are likely to be persistent.

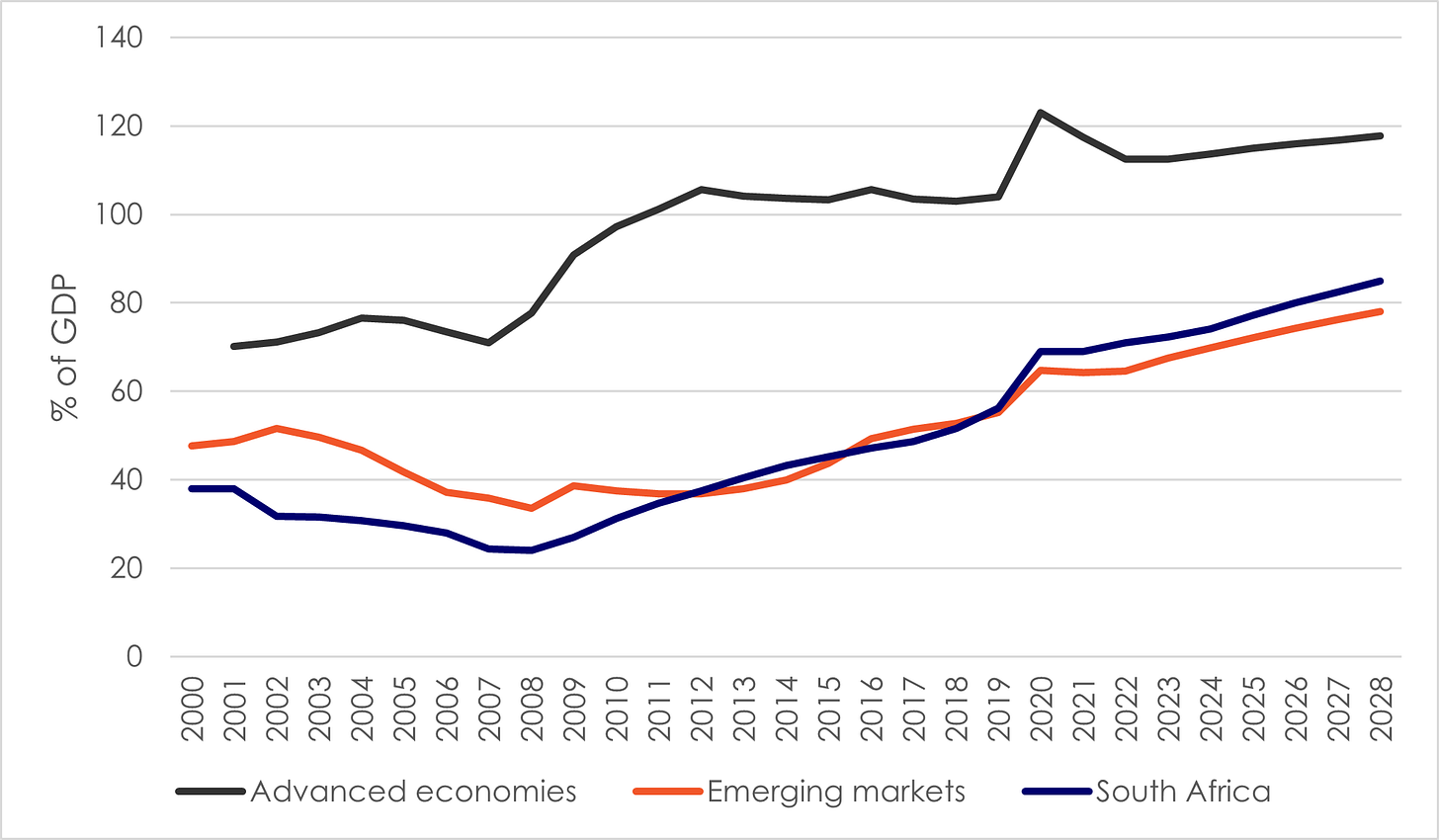

Debt as % of GDP is at elevated levels in advanced economies, emerging markets and South Africa

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, 2023

The public debt session focused on high public debt. The main paper in this theme was from Barry Eichengreen, a highly cited economist and economic historian, and Serkan Arslanalp. It is available here. It explores global high public debt levels.

They put forward the following main thoughts on high public debts:

· High public debts are a new reality.

· The political viability of achieving a persistent high primary budget surpluses is quite low. This means that public debt are likely to remain high for the foreseeable future.

· In most countries (South Africa being the notable exception), interest rate - growth dynamics are favourable. But it is difficult (in Eichengreen’s view) to see how real interest rates could come down. The paper echoes Jones in the view that faster global growth is unlikely – and Eichengreen’s view is that AI will take a while to translate in faster aggregate growth.

· Other ways of structurally reducing debt are off the table. Inflation is not a sustainable way of reducing high public debt – only unanticipated inflation could achieve this and that is very difficult, while financial repression as a means to reduce debt is not sustainable.

Paper 3: Have there been structural shifts in global growth?

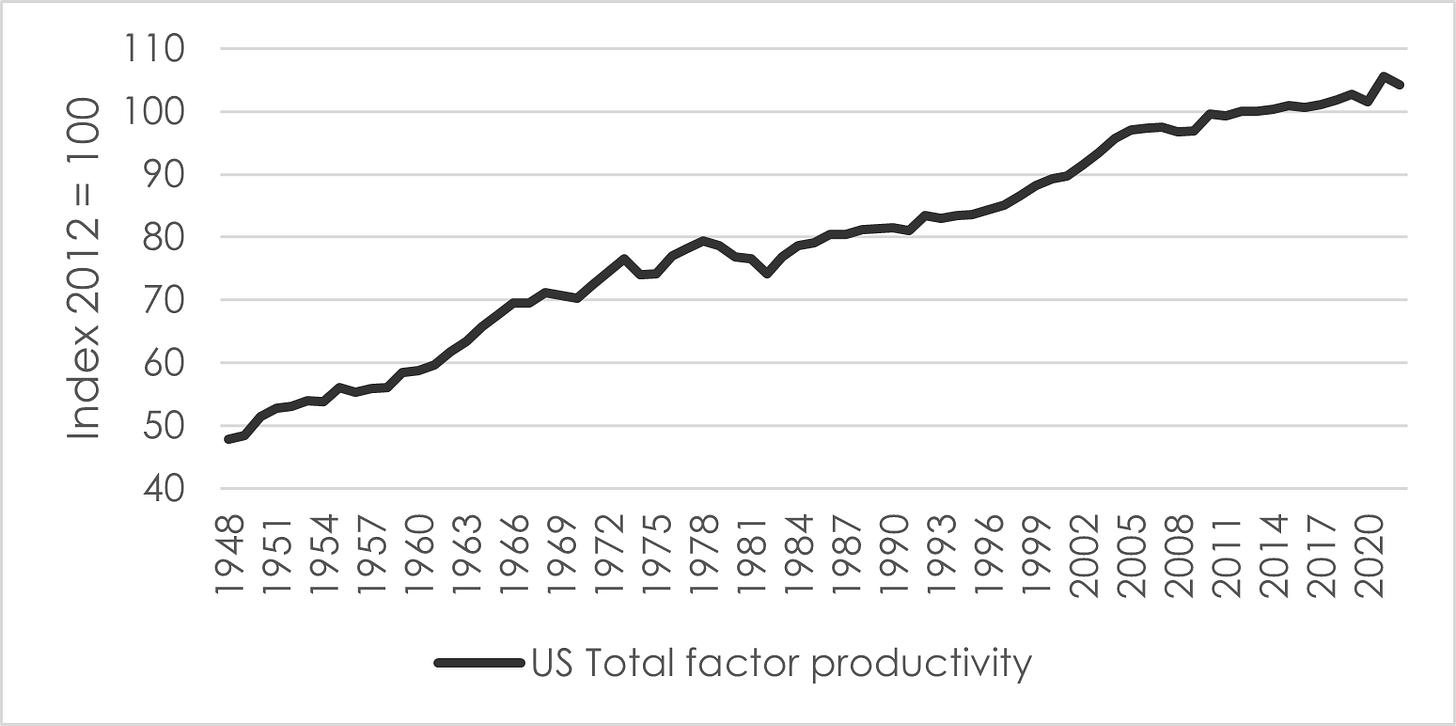

Charles Jones, a prolific author on economic growth, spoke to structural shifts in economic growth. (His slides are here and the paper that he based his talk on is here). He highlighted the slowdown in productivity growth in the US.

His approach to looking at growth is in the semi-endogenous growth tradition, one of Paul Romer contributions that won him the 2018 economics equivalent of the Nobel Prize. This tradition is (slightly) different from traditional growth theory. It focuses on ideas rather than technology. A new idea can be used by a number of people at the same time (it is “non-rivalrous”). He gives examples of ideas as a new farming technique, faster computers, or an advance in solar panel efficiency. An idea, like a new farming technique, can spread quickly. Ideas do not need to be country specific. And the best ideas are difficult to patent, so they can spread quickly. This departs from a lot of growth theory that tries to show that country specific factors (e.g., country specific research and development, education levels etc.) drive productivity growth.

In his Jackson Hole talk, Jones grapples with a deep question: have we run out of new ideas? And if we have, does this mean economic growth will start slowing forever? For the United States to maintain economic growth of 2%, ever-rising resources have to be expended in R&D. This is the “Red Queen theory”, based on the character in Alice in Wonderland, which is that we have to run faster and faster to stay in the same place. He has a slide showing how total factor productivity in the US has stagnated from 2010.

United States total factor productivity has slowed

Private business sector

1990-2003: 1.1%

2003-2022: 0.6%

Manufacturing 1990-2003: 1.6% 2003-2021: 0.4%

Source: Jones (2023), Krutham, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

On the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in long-term economic growth, building on some of his earlier work, his view is that AI is very good at making existing processes run better. But AI does not generate new ideas, and so is not growth enhancing. The consequence is that US growth may be entering a period of structurally low growth.

Conclusion

All in all - what did we learn? Not a lot but then Jackson Hole is a good annual stocktake of what is happening. This year was no different - it told us that everyone is worried about debt, growth and the capacity of banks to absorb increased issuance. Certainly things we worry about here in South Africa too.