A race ...

Rising interest rates lead to improved bank profitability. But as the economy deteriorates, for how long?

Macro backdrop

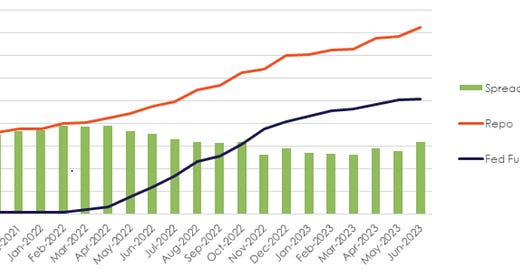

The theme of 2023 continues - global and domestic interest rates are rising at a rapid pace – US rates have risen the fastest in recorded history. The speed at which global (and domestic) macro rebalancing is taking place is unprecedented. The Sarb is raising fast but not as fast as the rest of the world. Our macro forecast is that there will be one more interest rate hike of 25bps to take us to 8.5% and then unchanged until 2025. This does suggest that the positive impact of higher rate on banks’ profitability will come to an end, and rising impairments and weak lending conditions through 2024 will cause pressure on bank profitability.

Figure 1 Fed funds and repo rate

Rising interest rates should be positive overall for bank profitability but this is a new world. As we covered in our previous note on the Silicon Valley Bank collapse, a sharp rise in interest rates also leads to asset repricing, which can have significant consequences as interest-rate risk materializes.

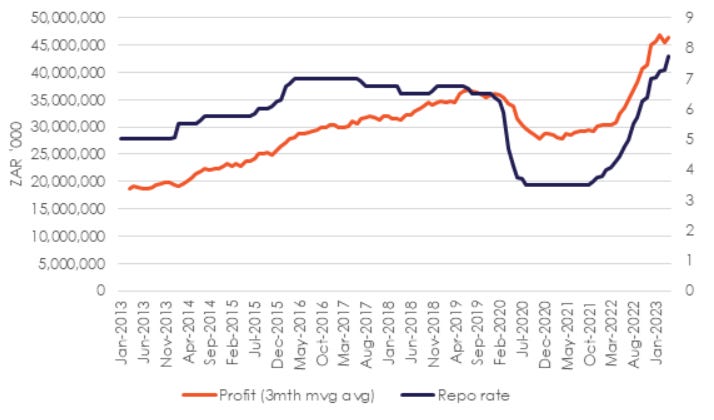

As we note in Figure 2, bank profits may have peaked, suggesting that there are other channels through which the interest rate cycle affects bank: funding costs, impairments, growth and inflation effect, capital flow effects and balance sheet effects.

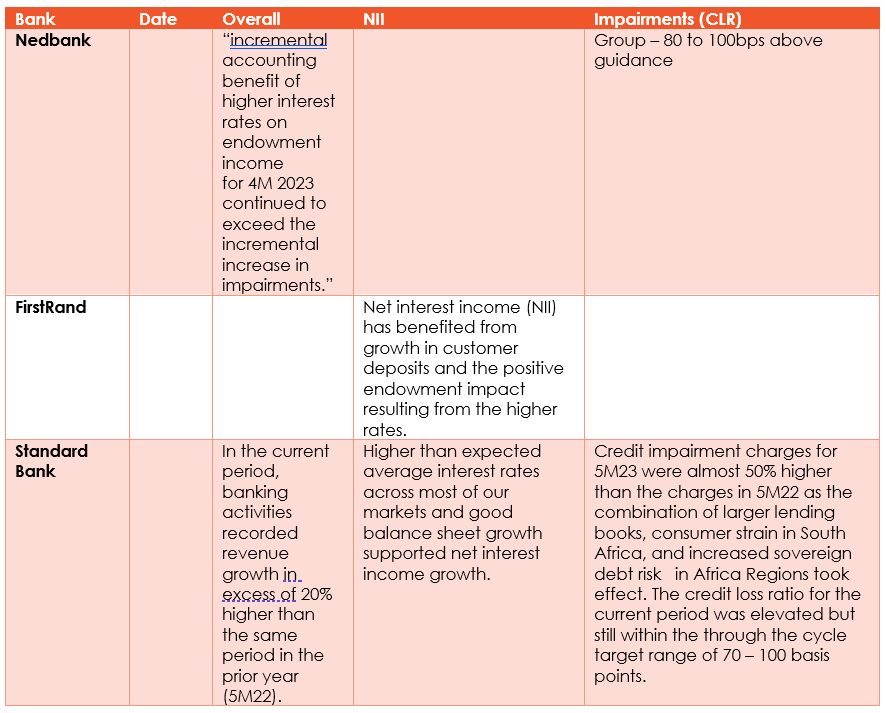

Trading updates from the big four suggest that it is indeed a race – Standard Bank note that banking revenue growth was 20% up, but that impairments were up 50%. Nedbank carefully couch their wording but suggest that interest rate effects are outweighing impairment effects. FirstRand indicated that NII is up but notes higher funding costs. (The trading updates are provided in Table 1 at the end of this section).

As we note in Figure 3, bank profits may have peaked and indeed with the repo cycle also peaking, the negative second-round effects may begin to weigh on overall profitability. These include higher funding costs, rising impairments, weaker growth and lower inflation, capital flow effects and balance sheet effects. We briefly unpack each of these below.

Figure 2: Bank profitability has risen strongly, buy may be reaching a peak

What is the impact of the rates cycle on banks?

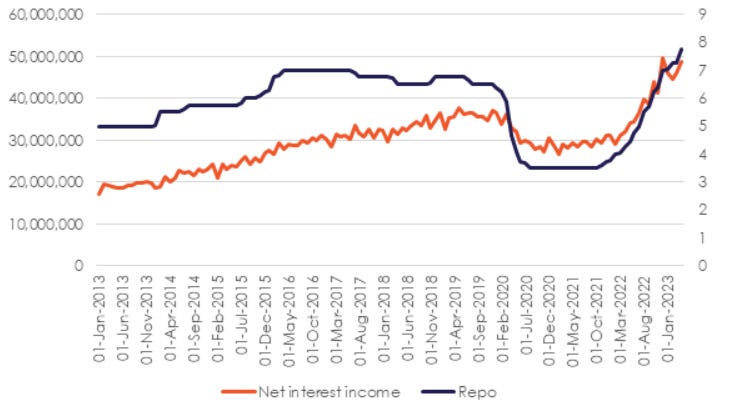

Channel 1: Net interest income

Unsurprisingly, net interest income follows the repo cycle reasonably closely. Rising interest rates have led to an increase in overall net interest earned.

Figure 3: Net interest income has risen with the upward cycle of the repo rate

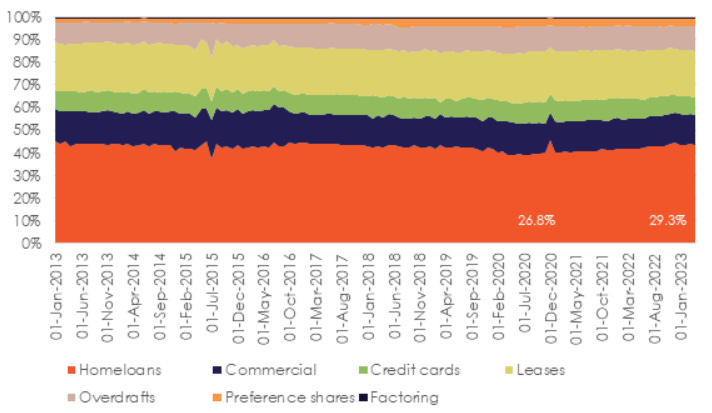

Figure 4 Interest income by type of loan/advance has also trended toward homeloans

The interest income by the type of loan also reflects overall credit conditions. Interest earned on homeloans has trended marginally upwards, rising from 26.8% of interest income in mid-2020 to 29.3% of all interest income in 2023.

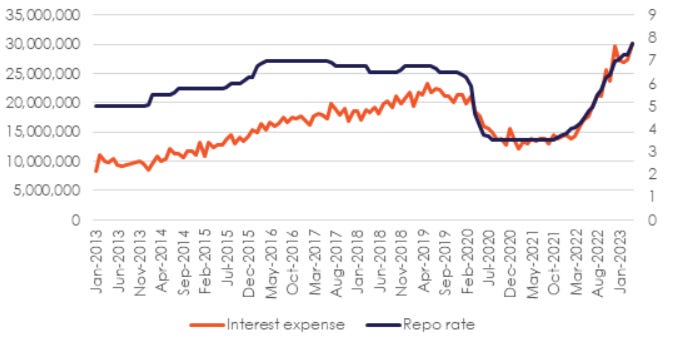

Channel 2: Funding costs (interest expense)

The second channel is through bank funding costs. Depending on how a bank funds itself (lazy deposits which can reset slower or short-dated NCDs, which track overnight rates), the impact of a rising rate cycle can differ quite significant bank-by-bank. Interest expenses have risen sharply on aggregate, reflecting relatively short-dated, interest-sensitive funding by banks.

Figure 5: Cost of funds (Interest expense) vs repo rate

Figure 6: Deposit growth (average y-o-y) was positive in 2022…

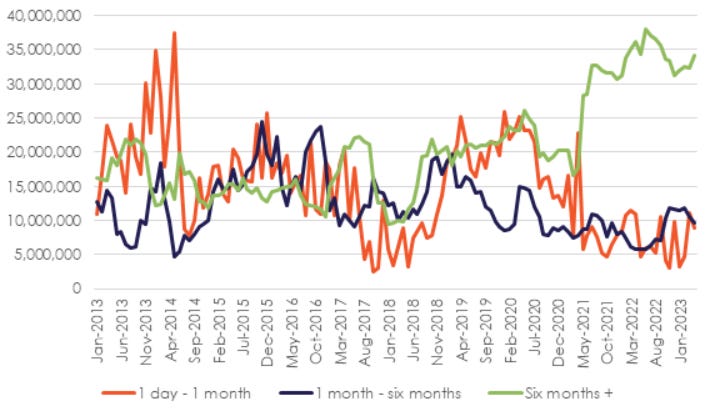

Figure 7 … led by longer term deposits (‘000)

Rising interest rates have also, according to the trading updates, encouraged increased bank deposits. In particular, long-dated deposits (six months plus) have risen strongly as depositors see the benefits of higher rates and wish to lock them in (see Figure 7).

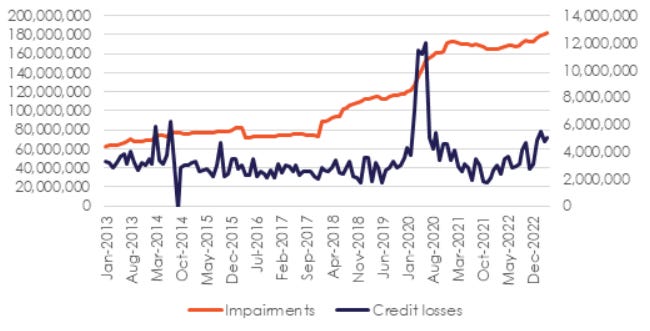

Channel 3: Impairments and credit losses

The third channel that rising rates can impact a bank is through impairments. The relationship is, however, complex. Interest rate upswings are generally associated with business cycle upswings – generally, the central bank is trying to dampen the credit cycle. Indeed, strong credit growth, falling impairments and rising interest rates generally are contemporaneous because they all reflect the same underlying economic situation – which is a strong, overheating economy. In our view, this interest rate cycle is significantly different. The current rising inflation has very little to do with a strong economy and much more to do with second-round effects from loadshedding, together with rising global rates. Indeed, the Sarb is tightening monetary policy during a very weak economy.

Both the annual results season and the earnings updates from the banks highlighted significant additional provisions for impairments. The May banking monitor dug a little deeper into the impairments trend. Both impairments and credit losses are rising and over time with the weaker economy and higher rates are likely to continue to be significant.

Figure 8 Impairments and credit losses are both trending upwards (‘000)

The impairments data is the one to watch. The weakening economy and feed-through to credit losses will inevitably put bank profitability under pressure.

Channel 4: Balance sheet growth

Figure 9 Private sector credit extension (y-o-y change) is easing

Rising rates have the effect of dampening credit growth – although our discussions with bankers suggest that the quality of credit growth is substantially better now (it is nearly the top of the interest cycle and those that can afford to borrow now are only the strong credits). Annual growth in PSCE slowed further to a 3-month low of 6.8% in May from 7.1% in April. This was a tad lower than the consensus estimate of 6.9% while we expected the print to remain unchanged.

Investment spending was quite a bit stronger than expected moving from -11.7% y-o-y to +3.0% y-o-y, while mortgage growth was weaker than expected (now the weakest since September last year at 6.1% y-o-y) but offset marginally by better instalment credit. The negative shock came from a collapse in short-term borrowing in “other”.

Overall real household credit growth was 0.3% y-o-y from 0.2% previously while real corporate credit growth was 0.5% from 0.3% previously.

Mortgages. Elevated costs of living and increased borrowing as well as debt-servicing costs continue to corrode affordability, especially in the lower-income group. However, price growth remains well supported in the lower end while property values have declined significantly in properties valued above R5.5m/ Supply of properties has trended upwards thus far in 2023 and is higher on a year-on-year basis. In contrast, demand is declining reflecting the challenges faced by consumers Unsurprisingly, the FNB House Price index growth continued to decline in May at an average of 1.9% (y-o-y) from 2.1% in April.

Vehicle asset finance. The squeeze on middle-class disposable incomes reflected in decline in Q1-23 in both VAF (-8%) and home loans (-4%) – from flat growth in Q4-22. Rates of new defaults (RNDs) on such loans continued to rise at 22% for VAF and 32% for home loans.

Unsecured credit. Current balance on all loans rose 1.9% q-o-q at R2.32 trillion, with most loan products remaining relatively flat. Home loans and credit card products had the largest increases in current balance, with balances increasing by R27.5bn (2.4% q-o-q) and R6.4bn (2.7% q-o-q).

Defaults and overdue balances are up q-o-q for the first time since Covid, with total overdue balances increasing by 3% q-o-q.

Figure 10 There is a slow shift towards corporate lending

Table 1 Trading updates - (copied verbatim)

Overall

Overall, our conclusions is that bank profitability has been buoyed by rising interest rates. As rates plateau, and impairments rise and funding costs remain elevated, the outlook for profitability looks somewhat murky. Banks hav indicated willingness to lend to strong credit (particularly on the back of energy market reforms) and this may support balance sheet expansion in 2024 and 2025, but at this stage, the outlook is for a difficult next year.

AGM Watch

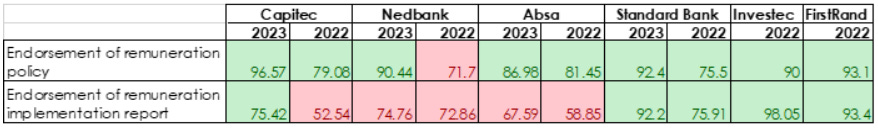

Bank AGMs this year were overall less fractious than the last two years, particularly on remuneration (held from late May to mid June for Nedbank, Absa and Standard Bank). There was a marked improvement in votes in support of remuneration policies and implementation:

Notably, Capitec managed to turn around a very negative view last year to scrape above the 75% threshold. Nedbank fell just short of the threshold, though overall there was better shareholder support than last year. Standard Bank also marked a significant improvement.

The 75% threshold is needed to avoid having to engage with shareholders to discuss remuneration issues. This engagement has become fairly nominal after previous engagements saw few shareholders taking up the opportunity. The temptation is to conclude that remuneration votes are not fully well considered. As always, however, there are a mixed bag of investors and buy side analysts, some of whom are very well considered.

Temperatures dramatically escalated during the Covid period where performance on key metrics meant many option schemes were left deep under water. In several cases, directors used discretionary space allowed by policies to introduce new schemes or summarily change vesting conditions so as to ensure executives were well remunerated through the Covid period. The obvious argument was that retention was key during the period and incentives needed to drive hard work in managing the crisis.

Investors, of course, saw it differently and decried the misalignment of shareholder and executive outcomes during the crisis. That triggered heightened shareholder scrutiny of remuneration policies, a genie that is unlikely to be put back in the bag. While proxy advisors are often blamed for the turn of institutions against certain remuneration practices, we’ve found that fund managers and sell side analysts are paying more direct attention to practices than in the past. This genie will not go back into the bottle.

This should place renewed pressure on remuneration committees to engage shareholders and ensure appropriate consideration of their concerns. We’ve experienced several bank directors dismissing those concerns as ill informed – but at the same time, fund managers have bent our ears about the “arrogance” of those same directors. This misalignment needs some reconciliation. While the lack of engagement in consultations post negative votes is seen as shareholder apathy by Remcos, shareholders tell us they stopped engaging because it made no difference to the practices they objected to, with Remcos merely doubling down.

The risk here is that shareholders mount more pressure for binding rather than advisory votes, or at least more binding consequences such as a “two strike rule” in Australia that requires a “spill resolution” to be proposed to vote out directors. This has clearly inspired provisions in the 2021 Companies Amendment Bill that would require the Remco to stand for reelection in the event of two strikes.

So while boards may groan at the consultation and reporting consequences of a negative vote, we think it is important to take shareholder concerns seriously and interrogate the practices that are at the heart of the problem (which is, broadly, any whiff of discretion). Without a genuine effort to reconcile their concerns, more strenuous regulatory consequences may well come, lobbied by frustrated shareholders.

Perhaps the real question for Remcos to ponder is how remuneration should be structured for the next crisis. Is there a non-discretionary mechanism that could be created? Should there be? Or should the idea that executives can escape the fate of shareholders in the event of disaster be consigned to history?

Basel developments: Recovery and resolution

We have reflected in recent banking monitors on the impact of the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse on the path of regulatory reform. Will it lead to a new plethora of regulations, particularly on resolution?

Reading the latest statement from the Financial Stability Board, the apex committee that brings together the Basel Committee, the International Organisation of Securities Organisations and the International Assoociation of Insurance Supervisors, we think not.

It is a bit of sniffy statement, noting that: “Prior to these events, the FSB had already planned to conduct a peer review on the overall implementation of the too-big-to-fail reforms in Switzerland, and it expects to publish its findings by early 2024.” One might expect that the FSB will take a route that revenge is a dish best served cold… one can expect a rather harsh peer review as the international community is less than pleased at how Switzerland has implemented internationally agreed recovery and resolution standards.

They flag a review of how supervisors implement the international standards. South Africa, of course, passed its own FSB review with flying colours. The only niggle is the difference between point of resolution and point of non-viability… but perhaps the renewed focus on the issue with lead to guidance from Sarb on how this will be implemented in practice.

Climate risks

On other areas, the FSB highlighted the onward march of the climate risk agenda. They (and we) are particularly pleased that the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) has finalised its climate-related and general sustainability-related disclosure standards, which will serve as a global framework for sustainability disclosures. The FSB (and we) look forward to the International Organization of Securities Commissions consideration of endorsement of the standards. This will hopefully bring together what are significantly disparate areas. Our own work on this area also marches forward relentlessly (some of it here).

RCAPS

As part of its Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP), the Basel Committee regularly undertakes assessments of South Africa’s adherence to Basel standards. The Committee found the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) regime to be largely compliant and the large exposures framework to be fully compliant. On the NSFR implementation regime, three out of four components were compliant for the criteria of scope, minimum requirements and application issues, required stable funding, and disclosure requirements, while the available stable funding component has been assessed as largely compliant. Full compliance is expected to be reached by January 01, 2028, which is as expected as South Africa slowly moves toward full implementation of the NSFR.

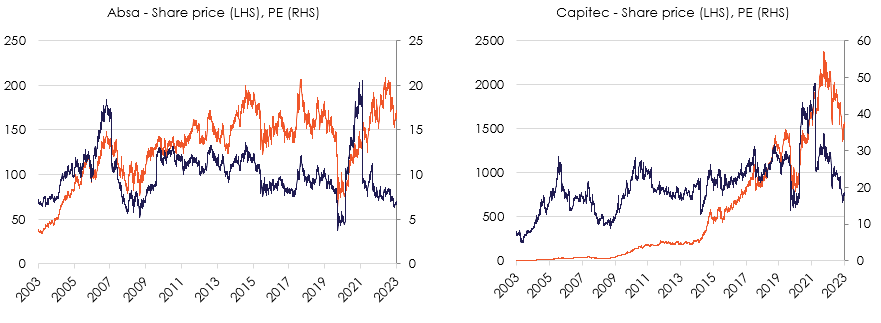

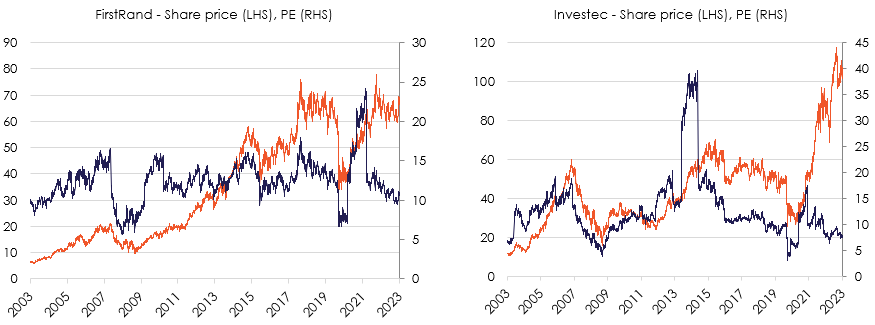

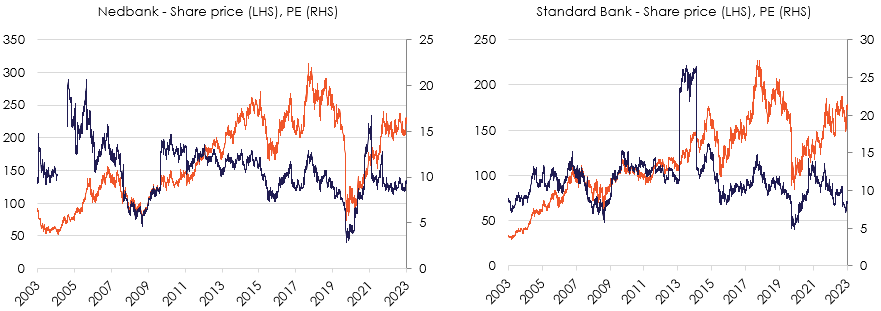

Share prices & PE ratios

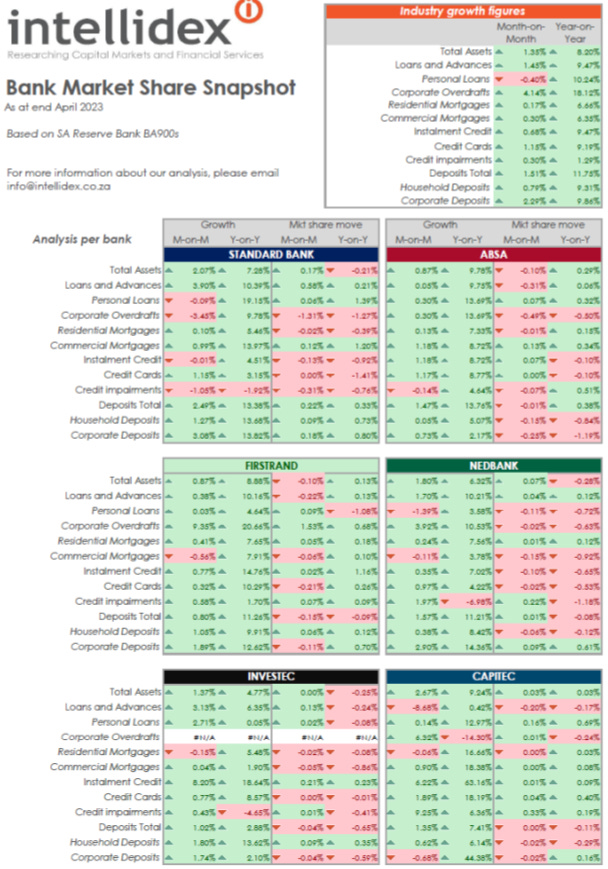

Market share changes

If you’re interested in our Banking Insights subscription, including Banking Monthly, BankAnalyser software, bank results flash notes and much more, please email research-distr@intellidex.co.za to discuss options

Disclaimer

This research report was issued by Intellidex (Pty) Ltd.

Intellidex aims to deliver impartial and objective assessments of securities, companies, or other subjects. This document is issued for information purposes only and is not an offer to purchase or sell investments or related financial instruments. Individuals should undertake their own analysis and/or seek professional advice based on their specific needs before purchasing or selling investments.

The information contained in this report is based on sources that Intellidex believes to be reliable, but Intellidex makes no representations or warranties regarding the completeness, accuracy or reliability of any information, facts, estimates, forecasts or opinions contained in this document. The information and opinions could change at any time without prior notice. Intellidex is under no obligation to inform any recipient of this document of any such changes.

No part of this report should be considered as a credit rating or ratings product, nor as ratings advice. Intellidex does not provide ratings on any sovereign or corporate entity for any client.

Intellidex, its directors, officers, staff, agents, or associates shall have no liability for any loss or damage of any nature arising from the use of this document.

Disclosure

The opinions or recommendations contained in this report represent the true views of the analyst(s) responsible for preparing the report. The analyst’s remuneration is not affected by the opinions or recommendations contained in this report, although his/her remuneration may be affected by the overall quality of their research, feedback from clients and the financial performance of Intellidex group entities.

Intellidex staff may hold positions in financial instruments or derivatives thereof which are discussed in this document. Trades by staff are subject to Intellidex’s code of conduct which can be obtained by emailing mail@intellidex.co.za.

Intellidex may have, or be seeking to have, a consulting or other professional relationship with the companies, sovereigns or individuals mentioned in this report. A copy of Intellidex’s conflicts of interest policy is available on request by emailing mail@intellidex.co.za. Relevant specific conflicts of interest will be listed here if they exist.

Copyright

© 2021. All rights reserved. This document is copyrighted to Intellidex (Pty) Ltd.

This report is only intended for the direct recipient of this report from an Intellidex group company employee and may not be distributed in any form without prior permission. Prior written permission must be obtained before using the content of this report in other forms including for media, commercial or non-commercial benefit.